Joint Ventures and Scab Workers: How the EV Transition is Challenging Unions

Ken Green

CEO & Founder

UnionTrack

Strong automotive unions are a legacy of the labor movement in the U.S. These unions have ensured highly-skilled automotive workers are prioritized and protected in an industry that is always evolving. Given the every-changing nature of the industry, this hasn’t always been easy.

The latest obstacle confronting industry unions in their mission to represent workers is the transition to the electric vehicle (EV) and how to guarantee union protections for workers at new EV plants.

“While the shift to electric vehicles represents an opportunity for improvement on numerous environmental fronts, it also represents a potential catastrophe for the economic well-being of many working people,” warns Paul Prescod, a socialist, teacher, and contributing editor at Jacobin magazine.

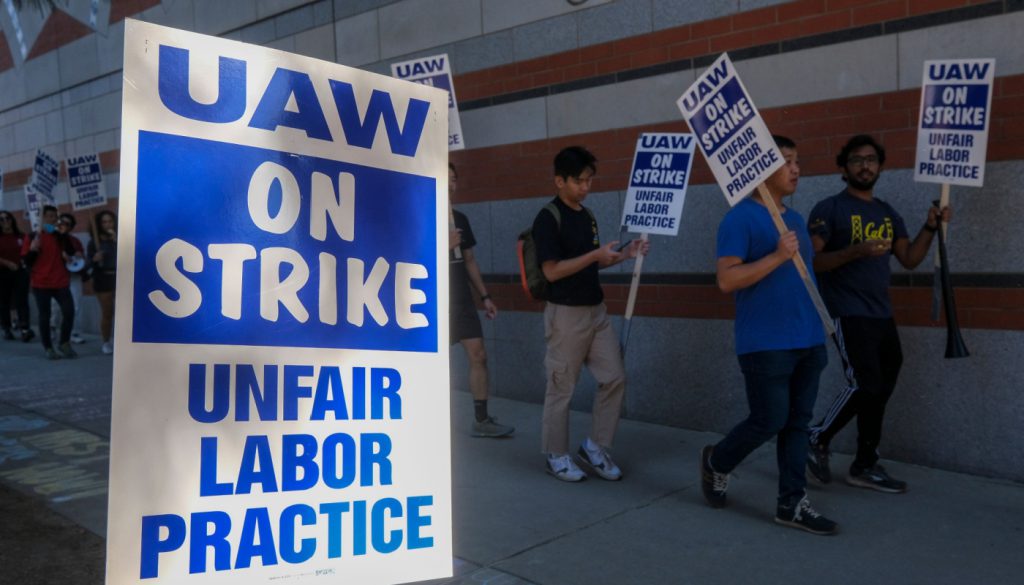

It falls to unions to prevent such disaster, and the International Union, United Automobile, Aerospace and Agricultural Implement Workers of America (UAW) — the largest industry union — is trying to draw a line in the sand as planned EV plants begin operations. There’s “no excuse” for automakers setting up nonunion EV shops, asserts UAW President Shawn Fain.

But holding that line isn’t easy.

UAW: Cover New EV Facilities by Master Contract

As they transition to manufacturing EVs, the big three automakers in the U.S. are opening new facilities for the production of these vehicles. Thousands of workers will be employed, but (if the companies have their way) without the protections of the current labor agreements between the UAW and the major U.S. automakers: Ford, GM, and Stellantis.

That’s because these facilities are actually joint ventures between the “big three” automakers and other companies. As such, management believes workers at each facility have to vote on joining the union and negotiate separate contracts for each facility.

The UAW sees it differently.

Union leadership is “pushing for a ‘just transition’ to electric vehicles (EVs) for auto workers, which includes the battery plants,” reports the BNN Newsroom team. In other words, every factory that opens would be covered by the national collective bargaining agreement. The coverage would help the union stay strong during this tumultuous time, and guarantee workers fair wages and safe working conditions as the new facilities open.

The Issue of Pay in New EV Plants is Already Contentious

Without the protection of a union contract, workers at the EV plants will earn less than those who work at traditional assembly plants.

Company executives argue that workers at EV plants should be paid less because they are doing work typically done by workers at third-party suppliers, says CNBC auto reporter Michael Wayland. These third-party workers make less than the traditional assembly workers who work for the automakers.

Workers at an Ultium Cells battery manufacturing plant in Warren, Ohio, recognized this injustice. They voted to organize with the UAW in December 2022. In doing so, they created the “first formal union at a major American electric vehicle or component factory not wholly owned by a Detroit automaker,” reports Ryan Erik King, a staff writer at Jalopnik.

It was a major victory for both the workers and the union. For the workers, it demonstrated their resolve to demand fair treatment.

“As the auto industry transitions to electric vehicles, new workers entering the auto sector at plants like Ultium are thinking about their value and worth,” said then-UAW President Ray Curry. “This vote shows that they want to be a part of maintaining the high standards and wages that UAW members have built in the auto industry.”

For the UAW, the win gives them some leverage to carry into current contract negotiations.

UAW Negotiating to Wrap EV Facilities Into New Contract

EV plant workers want to be unionized. That’s one critical message UAW leadership is taking into the contract talks for the new collective bargaining agreement. The old contract is set to expire on September 14, 2023, and the two sides have until then to reach an agreement.

One key area of contention is whether or not the EV plant workers should be covered by the national contract.

There’s no doubt these workers need a contract. Workers at the Ultium plant can earn up to $22 an hour while workers at assembly plants covered by a union contract earn more than $30 per hour, notes Carscoops editor Brad Anderson. There has also been twice the average rate of accidents at the battery plant, with 22 workers suffering injuries, reports Anderson.

But, if and until the master contract issue is resolved, the UAW is simultaneously negotiating a first contract with GM for the Ultium workers and the new contract. This division of assets puts a strain on union resources at a time when it should be funneling everything to win a favorable master contract. But the union is digging in to fight on all fronts at this pivotal moment for the automotive workers.

“A new industry is being born,” says Shawn Fain. “This is our defining moment. Our communities and our country deserve good, safe, living-wage union jobs.”

UAW Negotiates a Favorable Contract for Battery Plant Workers

In May 2023, after rejecting two tentative contract agreements, over 500 workers at the Clarios automobile battery manufacturing plant in Holland, Ohio, went on strike. The strike is to protest the company’s demands for a concessionary contract that would cut pay for workers. The Clarios strike made waves across the industry because of the production capacity at that facility.

According to the company’s website, the plant produces batteries for electric vehicles, hybrids, and internal combustion engines, supplying batteries for nearly one-third of the vehicles on the road. Given that, workers feel they have earned better pay and benefits.

“One of the problems is it’s a concessionary contract,” said UAW Local 12 President Bruce Baumhower when the workers went on strike. “Today’s economy is strong and our members have taken concessions when the economy wasn’t. They want a fair contract and the company isn’t willing. We’re not going backwards in today’s economy.”

Courtney Smith, a staff organizer at Labor Notes, explains some of those major concessions the company was pushing:

- Overtime pay changes. Overtime pay would kick in after a 40-hour week instead of after an 8-hour day.

- Schedule changes. Instead of five 8-hour shifts per week, workers would work a 2-2-3 schedule of 12-hour days.

- Incentive pay reductions. Workers would have to produce more to receive incentive pay.

All of these concessions would result in pay reductions for workers. To protect themselves from such terms and force the company to concede a more favorable contract, nearly all of the workers went on strike. “We’re not asking for the moon, we just want it to be a good place to work,” machine operator Andrew Hoertz told Smith.

Their tenacity paid off, even though the company hired scab workers to continue production during the strike. After about six weeks, a new contract was approved and the strike ended. That new contract includes a signing bonus, an annual pay raise each year over the life of the contract, and a resolution to the scheduling issue, report Andrew Bailey and Melissa Andrews at WTOL 11.

The labor market for the production of EV vehicles is only going to expand as the industry grows. Unions need to get in on the ground floor and insist that those new shops be unionized. That will require an all-hands-on-deck approach by automotive unions to spread awareness of the role unions play in improving working conditions and encourage workers at new facilities to organize.

Union leaders can use a communication platform like UnionTrack® ENGAGE® to engage members in this outreach. The tool allows users to share information in real time and manage outreach activities to reach as many workers as possible at new EV facilities.

Images used under license from Shutterstock.com.