Inside The WGA Writers Strike from the Labor Perspective

Ken Green

CEO & Founder

UnionTrack

While Hollywood writers are back at work and the strike is over, the new contract still needs to be ratified. Here’s a look at what went on over the past five months and what we can expect to see in the near future.

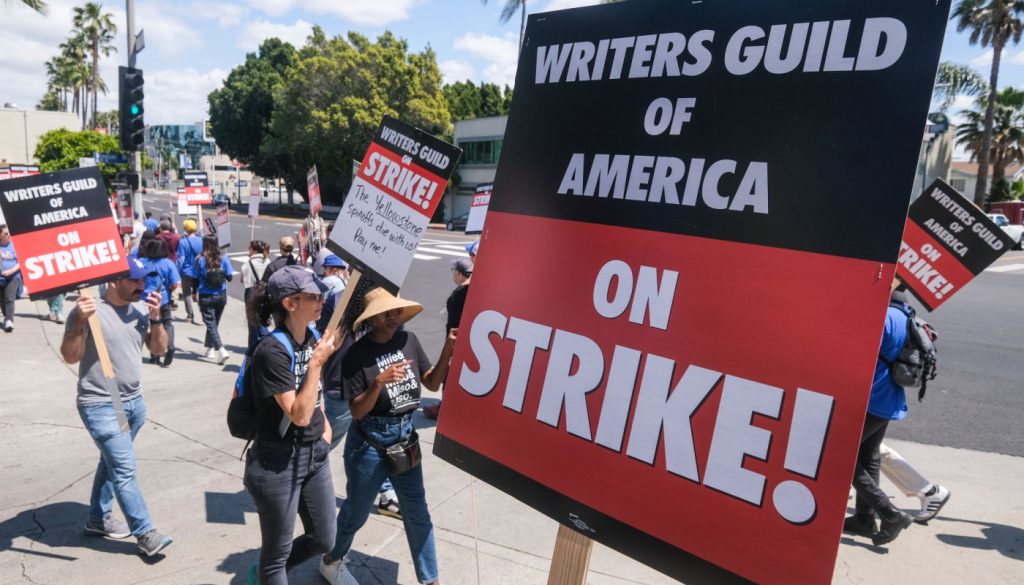

On May 2, 2023, nearly 11,500 television, movie, news, online, and radio writers, represented by the Writers Guild of America (WGA), went on strike after failing to negotiate a new contract with the Alliance of Motion Picture and Television Producers (AMPTP).

When the two sides couldn’t reach an agreement after six weeks of talks, eligible members voted 9,020 to 198 (nearly 98 percent) in favor of going on strike.

“These results set a new record for both participation and the percentage of support in a strike authorization vote,” tweeted WGA Captain Caroline Renard after the vote.

And they were still striking over four months later, demonstrating a determination to stand their ground and secure favorable terms in the new collective bargaining agreement. As one writer on the picket lines told Gene Maddaus, senior media reporter at Variety, “obviously we’re not backing down. They’re going to have to come up with something.”

What Issues Are at the Heart of Negotiations and the Strike?

Entertainment content writers have been greatly impacted by the adoption of technology and the evolution in the way people consume media. They are losing status and standing in writing rooms and, consequently, compensation even though studios are making money off their work. So now, maybe more than ever, writers are relying on their union to protect them through contract negotiations.

To that end, what issues are most critical to the writers in their new contract with AMPTP?

The Growth of Streaming Services is Changing How Writers Work and Get Paid

People’s media consumption habits have drastically shifted over the last few years. Increasingly more consumers are choosing to use streaming services instead of cable providers for their entertainment. This is costing writers jobs and income.

Writers are Making Less

Shows created for streaming services often have shorter seasons than broadcast television shows, which means less time writing. There is also a longer lag time between seasons, sometimes as much as a year for a streaming service show compared to a few months for a broadcast show, which means more down time. The end result is less work and less pay for television writers.

“With traditional TV models, jobs were lasting six months, nine months, a year,” says writer Amanda Mercedes. “I saw a writer the other day that said that her last job was four weeks, and that’s just not sustainable to be able to string together gigs in that way to make a living.”

According to a report by the WGA, median weekly writer-producer pay has declined 4 percent over the last 10 years. When adjusted for inflation, that’s a decline of 23 percent.

Screenwriters who write for streaming services are being paid movie-of-the-week rates because those films are being released directly through the platforms instead of through theaters. So, they are doing the same amount of work (writing for a full-length feature film) but getting paid significantly less.

The WGA report shows median pay for screenwriters hasn’t gone up since 2018. After adjusting for inflation, that’s a wage decline of 14 percent over the past five years.

Quite simply, writers are struggling to make a living.

“The livelihood of all writers is at stake,” says television writer Michael Jamin. “We take great satisfaction from our jobs and want to continue creating the stories that everyone loves – but we need to be able to make a living.”

Residuals are Disappearing

Not only has compensation for writing gone down per job, but streaming has also taken away residual payments from writers.

Traditionally, successful network shows were sold into syndication, generating residuals for writers. Those residuals are minimal to almost non-existent for streaming platforms. Content written and produced for streaming services stays available until the service decides to remove the content from the platform. This can be for years. In the meantime, writers are losing out on that income even though the providers are still making money on those shows and movies.

Also, because the process for calculating residuals isn’t transparent with streaming services, those that do get checks have no clue if they are being fairly or accurately paid.

“We have no idea how residual amounts are calculated because they do not tell us,” says TV writer, executive producer, and author Sheri Holman. “I got a check the other day for $8. What is even the point of that?”

Studios Want Fewer Writers in the Writing Room

Streaming services are also changing the format of writers’ rooms. For broadcast shows, groups of sometimes ten or more writers would convene for months to share ideas and learn the production process. But streaming services are changing that with mini rooms.

Mini rooms usually consist of a handful of writers who work for a few weeks, maybe a couple of months. Those writers are then excluded from the production process. “This makes it especially difficult for newer writers to gain the necessary experience to allow them to progress in their careers and also keeps writers from historically marginalized communities from equitable treatment,” writes B.J. Colangelo, lead evening news editor at /Film.

Workers are Concerned About AI Taking Their Jobs

Nobody knows exactly what role artificial intelligence will play in the writing process in the future, but nobody can argue that it won’t have some impact. That unknown is a cause of concern for writers.

“A scenario could arise in which an AI tool is used to generate an idea for a plot, or even a full script, and then a writer is hired to revise it, or punch it up,” writes Vox senior correspondent Alissa Wilkinson. “This would cut costs for the studios.” They could pay writers less since they aren’t turning in original scripts, but only adapting ideas, explains Wilkinson.

That’s why writers are insisting on strict rules for using AI to write scripts.

“They don’t want to rewrite material generated by AI, nor for AI to rewrite human-created scripts, and they want union-covered material to be excluded from training AI models,” explains Irina Ivanova, deputy U.S. news editor at Fortune.

Additionally, notes Washington Post reporter Erica Werner, writers “want to ensure that screenplays, scripts and other material they’ve written in the past will not be used to train AI systems.”

Insisting that artificial intelligence be addressed in the new contract is the only way the union can protect workers from the unknown consequences of further AI adoption in writing scripts.

Unfortunately for everyone, including the public, the two sides have been unable to negotiate a contract that meets these demands, making an already difficult financial situation worse for writers who haven’t worked in over four months.

Writers Struggle to Pay the Bills While on Strike, But Keep Showing Up on the Picket Lines

Being out on strike, especially for so long, is financially challenging for workers in an industry where pay is already unreliable at best.

While the WGA does have a strike fund to help writers financially during the strike, many workers have been forced to get creative at earning money with odd jobs, or what TV writer Brandi Nicole calls “survival jobs,” such as servers, substitute teachers, and retail workers.

But, as Nicole explains, getting even those jobs is complicated for writers because those who are in the middle of a project must be ready to get back to work as soon as the strike is over. This makes it difficult to find work because “companies can be hesitant to hire writers who may leave when they get another writing job,” notes journalist Aaron McDade.

To top it all off, striking workers do not qualify for food stamps.

These uncertainties have created food and housing insecurities for a lot of writers. That’s why they and the union have thrown their weight behind California Senate Bill 799 which would give unemployment insurance to striking workers. The bill has passed through the legislature and is awaiting Governor Gavin Newsom’s signature.

Even in the face of all of these challenges, the writers are holding firm in their determination to have their concerns addressed in the new contract.

The Two Sides Have Reached a Tentative Agreement

They may finally be seeing the fruits of that labor.

The two sides returned to the table on September 20 and have spent long hours negotiating over the past three days. Though they have yet to reach an agreement, many striking writers are optimistic about a resolution.

“Negotiating is a lot better than not negotiating,” says television writer Aaron Ginsburg. “So after 100 days of them stonewalling us, any movement in that direction is positive.”

Turns out, that movement was very positive. As of September 24, the two sides reached a tentative labor agreement. Details have not yet been released, but the union says the deal is a win for its members.

“We can say, with great pride, that this deal is exceptional – with meaningful gains and protections for writers in every sector of the membership,” wrote the WGA in a message to members.

This is not the end of the strike. The new contract must first be ratified by the union’s board and members before the writers can get back to work.

In times like these, union leaders and strike organizers can use a tool like UnionTrack® ENGAGE® to communicate in real-time with members about the progress of negotiations and help keep members motivated to stand in solidarity until an agreement is reached.

Images used under license from Shutterstock.com.